“…Lehrer’s most recent project is a quartet of books called The Portrait Series, published by Bay Press in Seattle. In each volume, a man on the “wobbly line between brilliance and madness” narrates his biography. Brother Blue is an ordained minister and professional raconteur who dresses in clothes trimmed with butterflies. Charlie, a musician, has been in and out of mental institutions for 17 years. Nicky D. is a retired dockworker in Long Island City, Queens, who delivers ‘barbed commentary on familial duty, work, war, money, religion—and the best way to chop garlic.’ Claude, the adopted son of a French ambassador, earned degrees in art and medicine and endured a spate of homelessness.

The Portrait Series represents Mr. Lehrer’s first attempt to reach a mainstream audience. His early work was published in editions of under a thousand and sold to collectors who recognized the author’s place in a long tradition of typographic outlaws. Others considered him too far ahead of his time. When he showed his first book Versations to a dealer more than a decade ago, the man admired its artful density, then advised Mr. Lehrer, “Come back when you’re dead.”

Now the times are beginning to catch up to him… While Mr. Lehrer’s early books can seem as boisterous as a video arcade—one does not read them so much as attend their performance—The Portrait Series shows more typographic restraint. It also shamelessly offers the pleasures of voyeurism all good books afford. Who knows? Mr. Lehrer may finally have met the times halfway.”

The New York Times Book Review Julie Lasky

“In the four new publications by Lehrer… the implications of a new kind of literature are at last being pursued… The Portrait Series is articulated with enormous feeling and care by an author with an ear superbly attuned to the cadences of spoken language. Lehrer, unlike so many contemporary graphic stylists, begins from a deep engagement with content he has created himself…”

Frieze Magazine Rick Poynor

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

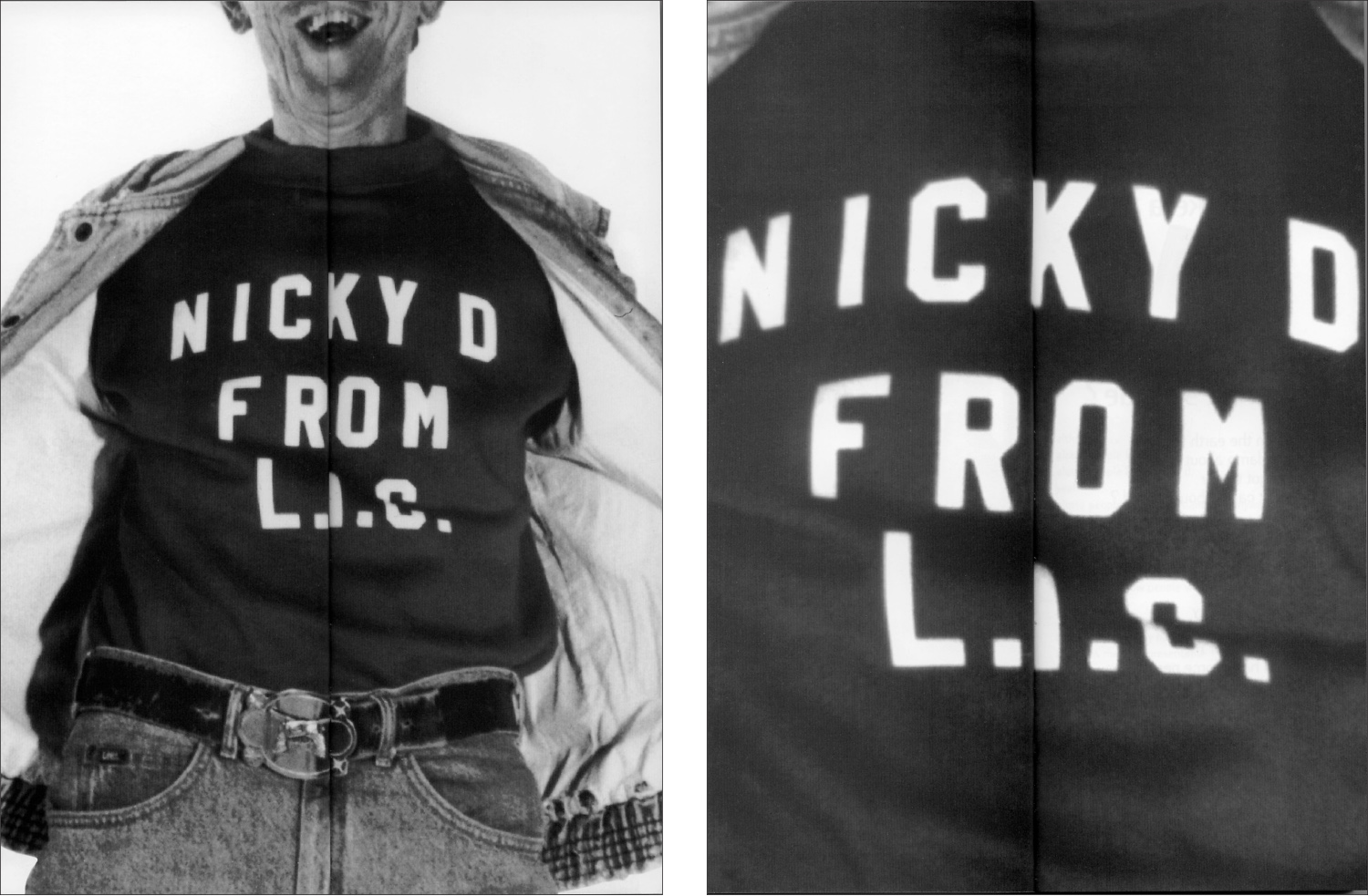

From the introduction to Nicky D. from L.I.C.: a narrative portrait of Nicholas DeTommaso

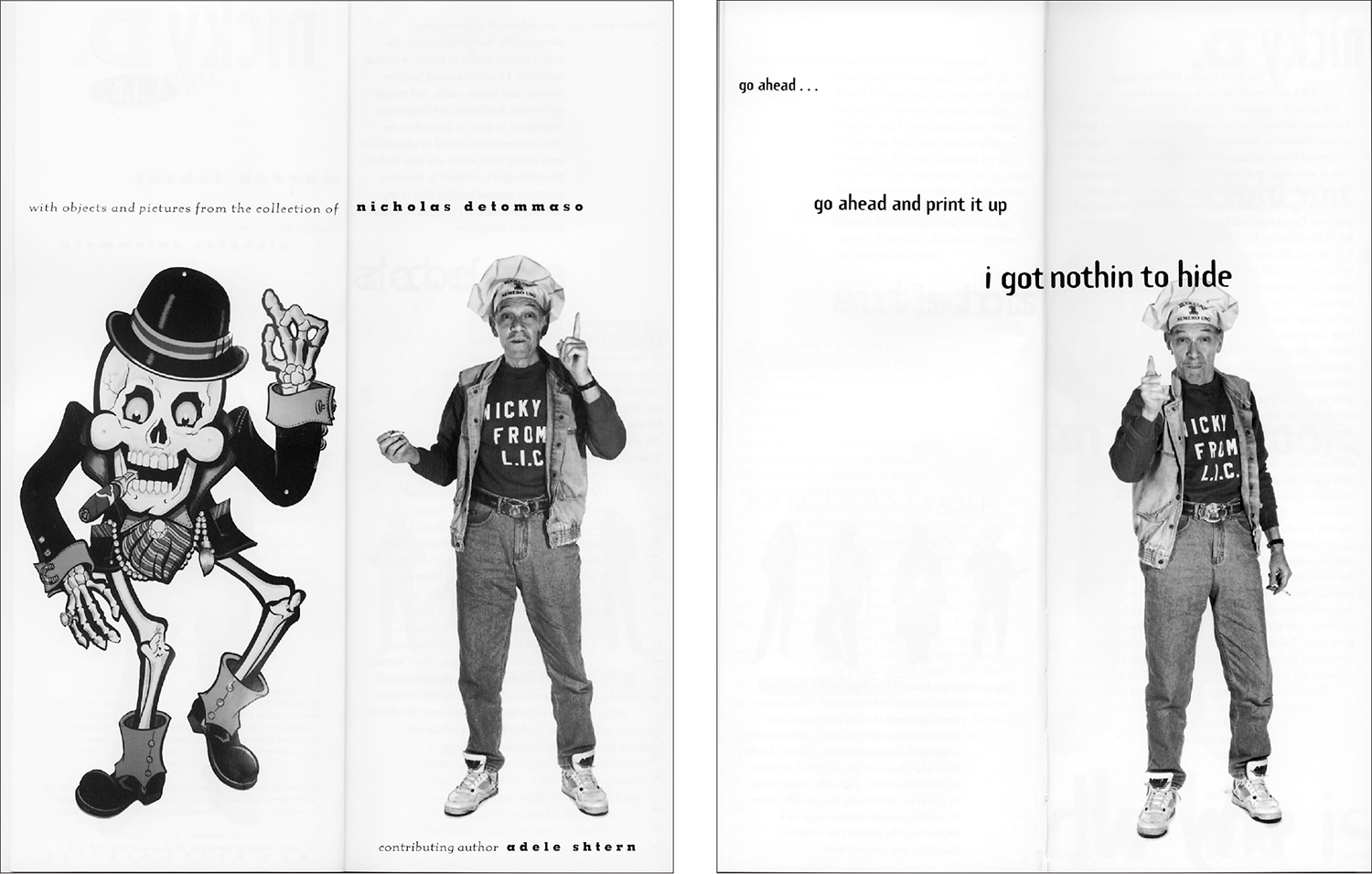

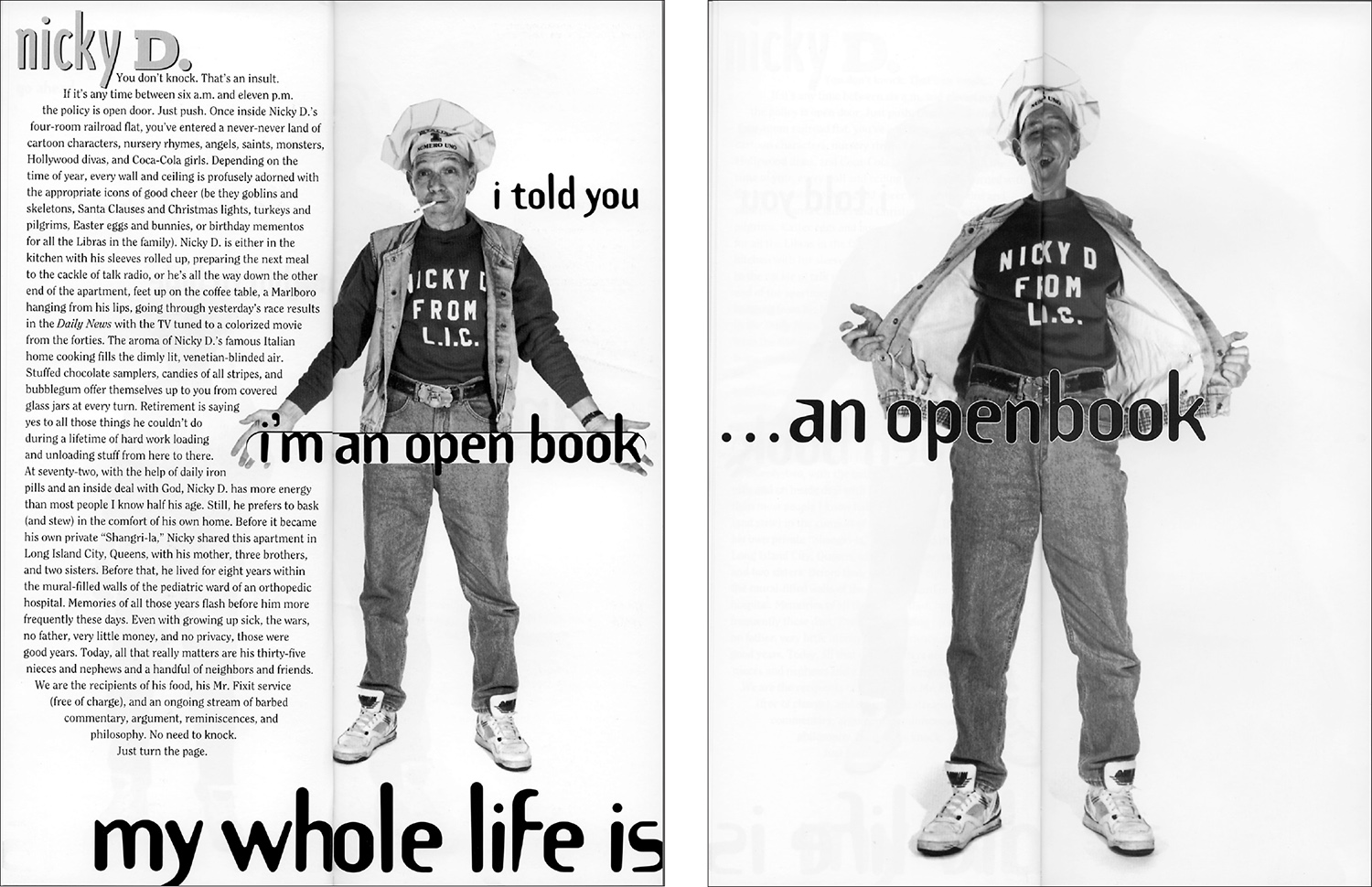

You don’t knock. That’s an insult. If it’s any time between six a.m. and eleven p.m. the policy is open door. Just push. Once inside Nicky D.’s four-room railroad flat, you’ve entered a never-never land of cartoon characters, nursery rhymes, angels, saints, monsters, Hollywood divas, and Coca-Cola girls. Depending on the time of year, every wall and ceiling is profusely adorned with the appropriate icons of good cheer (be they goblins and skeletons, Santa Clauses and Christmas lights, turkeys and pilgrims, Easter eggs and bunnies, or birthday mementos for all the Libras in the family).

Nicky D. is either in the kitchen with his sleeves rolled up, preparing the next meal to the cackle of talk radio, or he’s all the way down the other end of the apartment, feet up on the coffee table, a Marlboro hanging from his lips, going through yesterday’s race results in The Daily News with the TV tuned to a colorized movie from the forties. The aroma of Nicky D’s famous Italian home cooking fills the dimly lit, venetian-blinded air. Stuffed chocolate samplers, candies of all stripes, and bubblegum offer themselves up to you from covered glass jars at every turn. Retirement is saying yes to all those things he couldn’t do during a lifetime of hard work loading and unloading stuff from here to there.

At seventy-two, with the help of daily iron pills and an inside deal with God, Nicky D. has more energy than most people I know half his age. Still, he prefers to bask (and stew) in the comfort of his own home. Before it became his own private “Shangri-la,” Nicky shared this apartment in Long Island City, Queens, with his mother, three brothers, and two sisters. Before that, he lived for eight years within the mural-filled walls of the pediatric ward of an orthopedic hospital. Memories of all those years flash before him more frequently these days. Even with growing up sick, the wars, no father, very little money, and no privacy, those were good years.

Today, all that really matters are his thirty-five nieces and nephews and a handful of neighbors and friends. We are the recipients of his food, his Mr. Fixit service (free of charge), and an ongoing stream of barbed commentary, argument, reminiscences, and philosophy. No need to knock. Just turn the page.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

“The arrival of the first set of Warren Lehrer’s Portrait Series is something of an event… echoes of Henry Miller… vivid evocations of family life and history. Absolutely defining and unmistakable.”

JAB (Journal of Artists’ Books) Paul Zelevansky

“Each book in The Portrait Series is a vibrant visual and narrative biography of an eccentric, prismatic and resilient personality… Riveting! Lehrer defies categorization.”

Gannet Newspapers Linda Kaplan Wagner

“With The Portrait Series Lehrer continues his pioneering work in ‘visual literature’ in which the look of the words on the page is as important as the words themselves.”

Philadelphia City Paper David Warner

“As an undergraduate art major at Queens College of the City University of New York in the 1970s, Warren Lehrer experimented with drawings that combined words and images. He amassed, he says, ‘a whole stack of secret drawings I never showed anybody.’

Then one day he showed them to his painting teacher. ‘The teacher wagged his finger in my face and said, ‘You’re a really good student, but you’re barking up the wrong tree. Don’t ever combine words and images. They’re two different languages, and they should stay separate.’”

Mr. Lehrer recalls. ‘I left his office feeling like I’d been given a mission in life. And I’ve been combining words and images every since.’

Mr. Lehrer, now 40, is an associate professor of art at the State University of New York at Purchase. He teaches design, typography, book arts, performance art, and public art, as well as an interdisciplinary workshop for artists and writers.

Disregarding his professor’s admonition, Mr. Lehrer has combined words and images in a total of 10 books that defy conventional notions of writing and book making. His most recent effort is The Portrait Series, published by Bay Press, Inc. The series consists of four books, each a profile of a man, written by Mr. Lehrer, but presented as an autobiographical, first-person monologue. (Mr. Lehrer is at work on a series of portraits of women.)

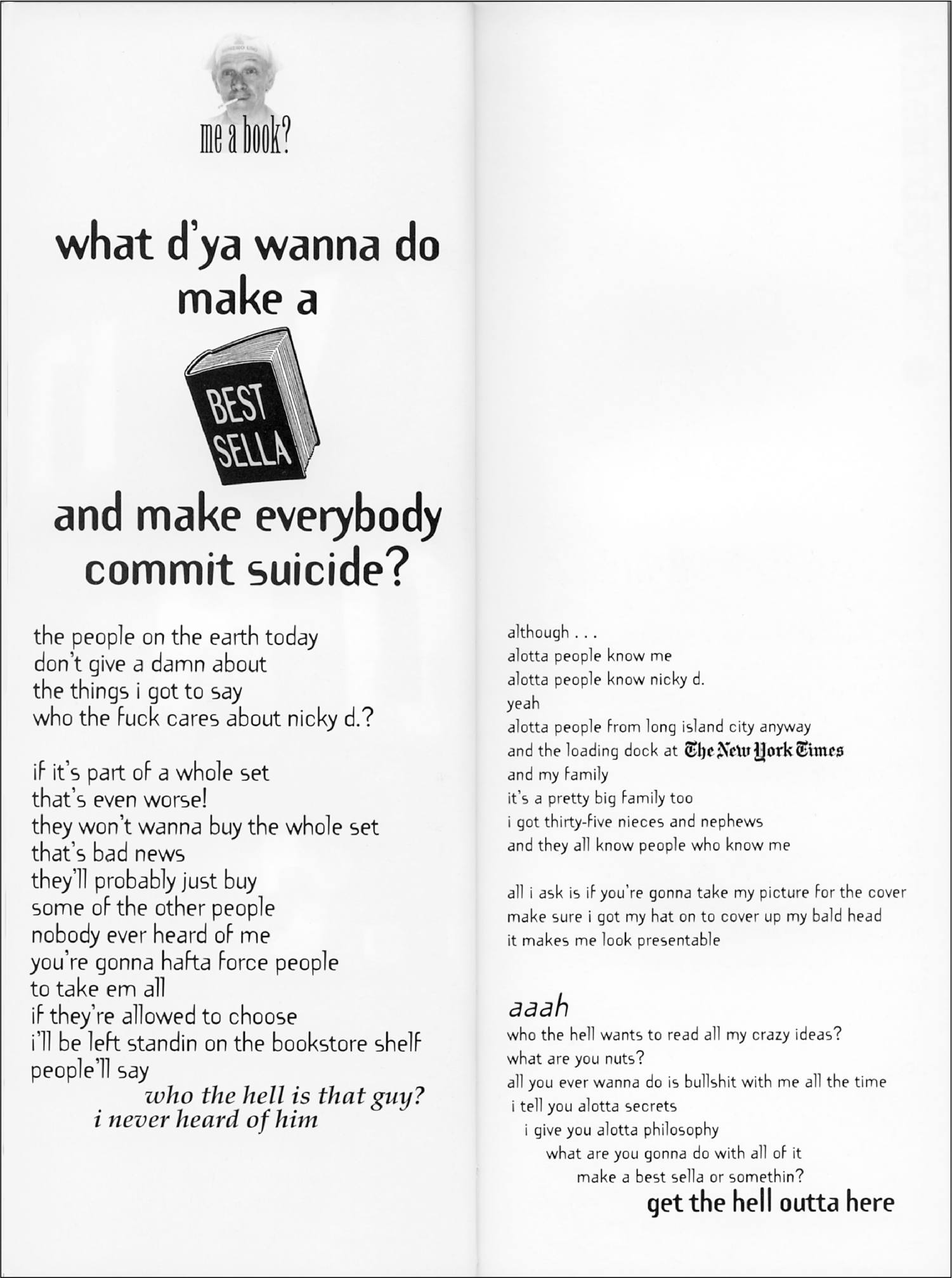

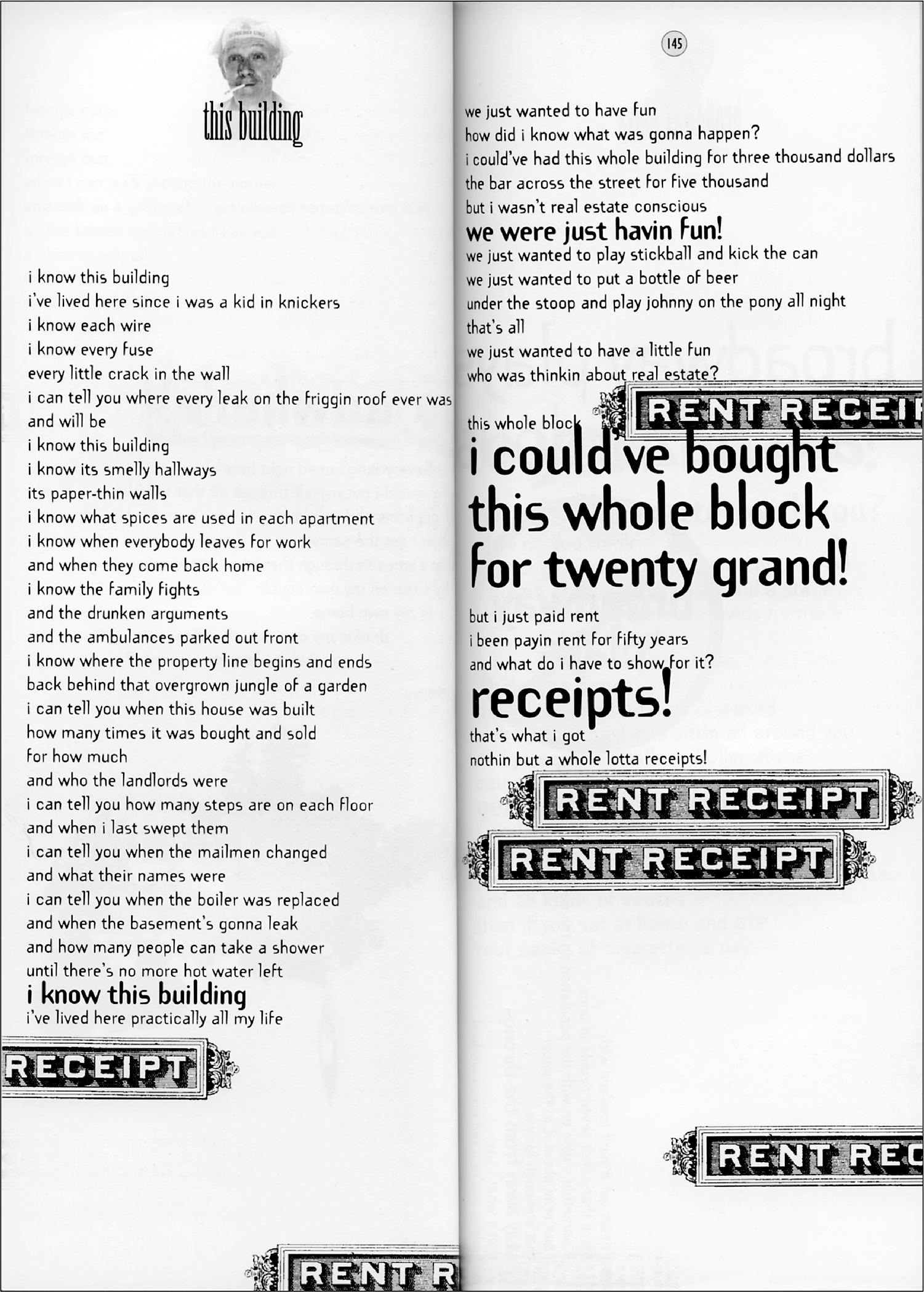

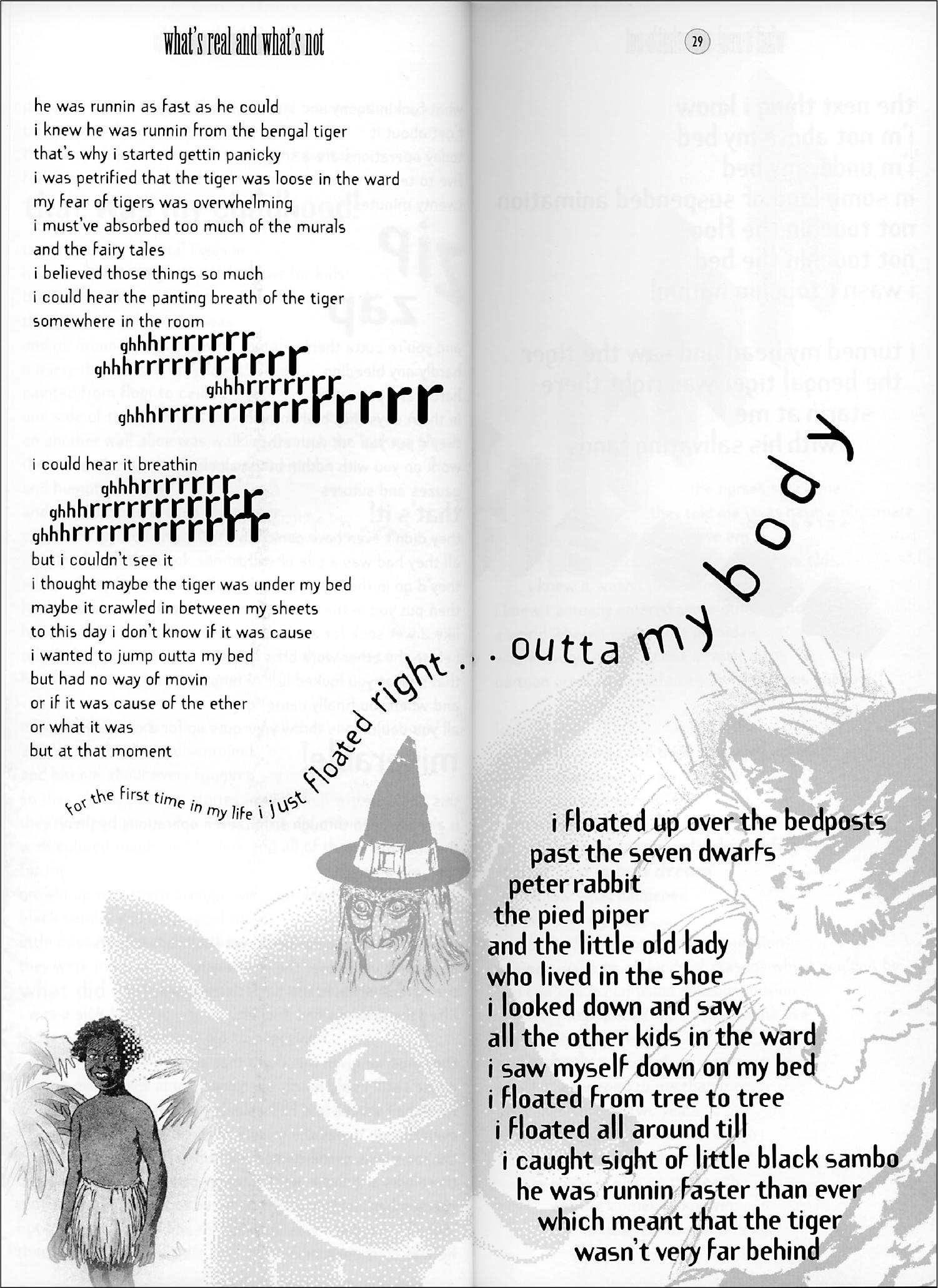

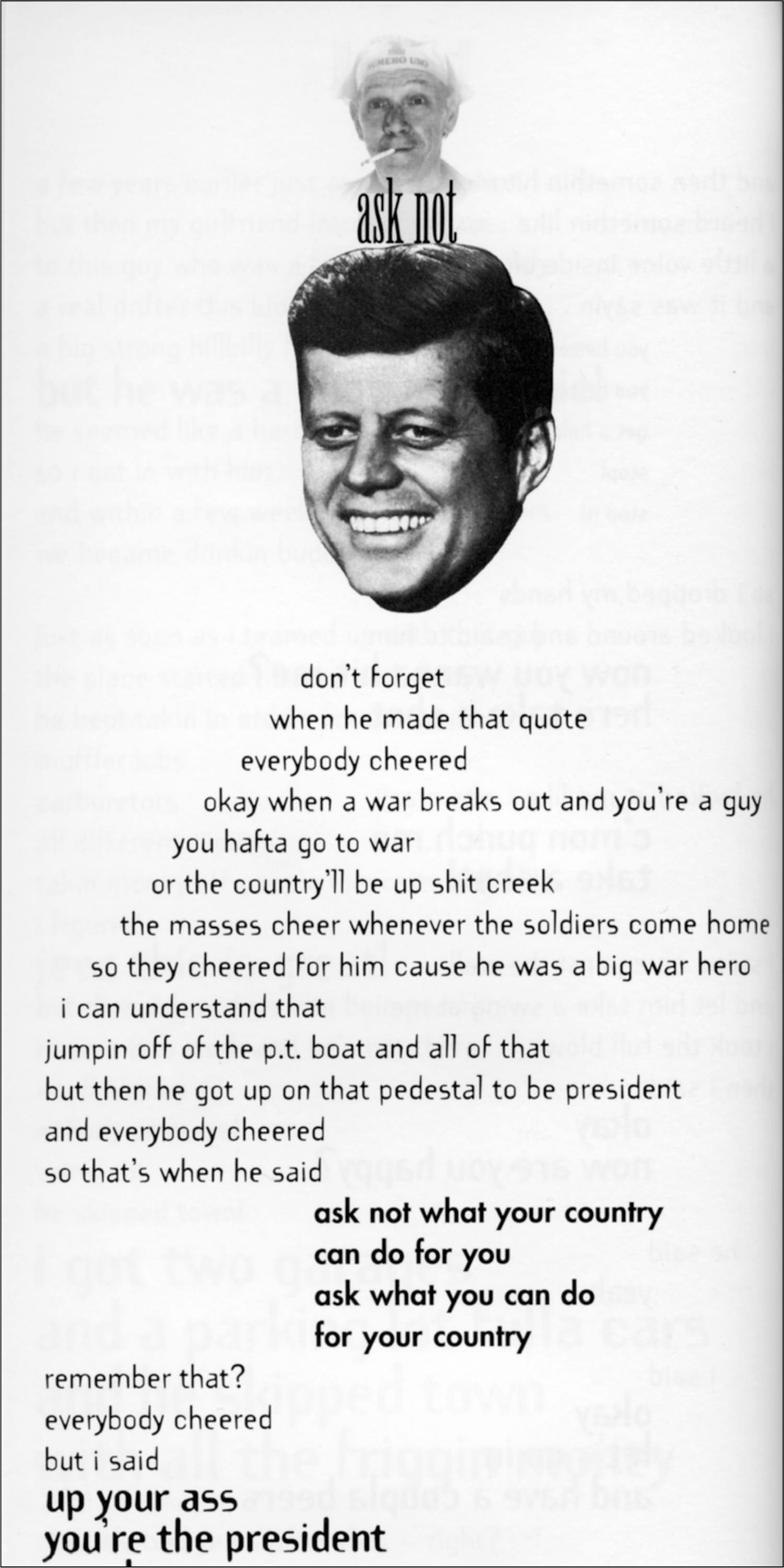

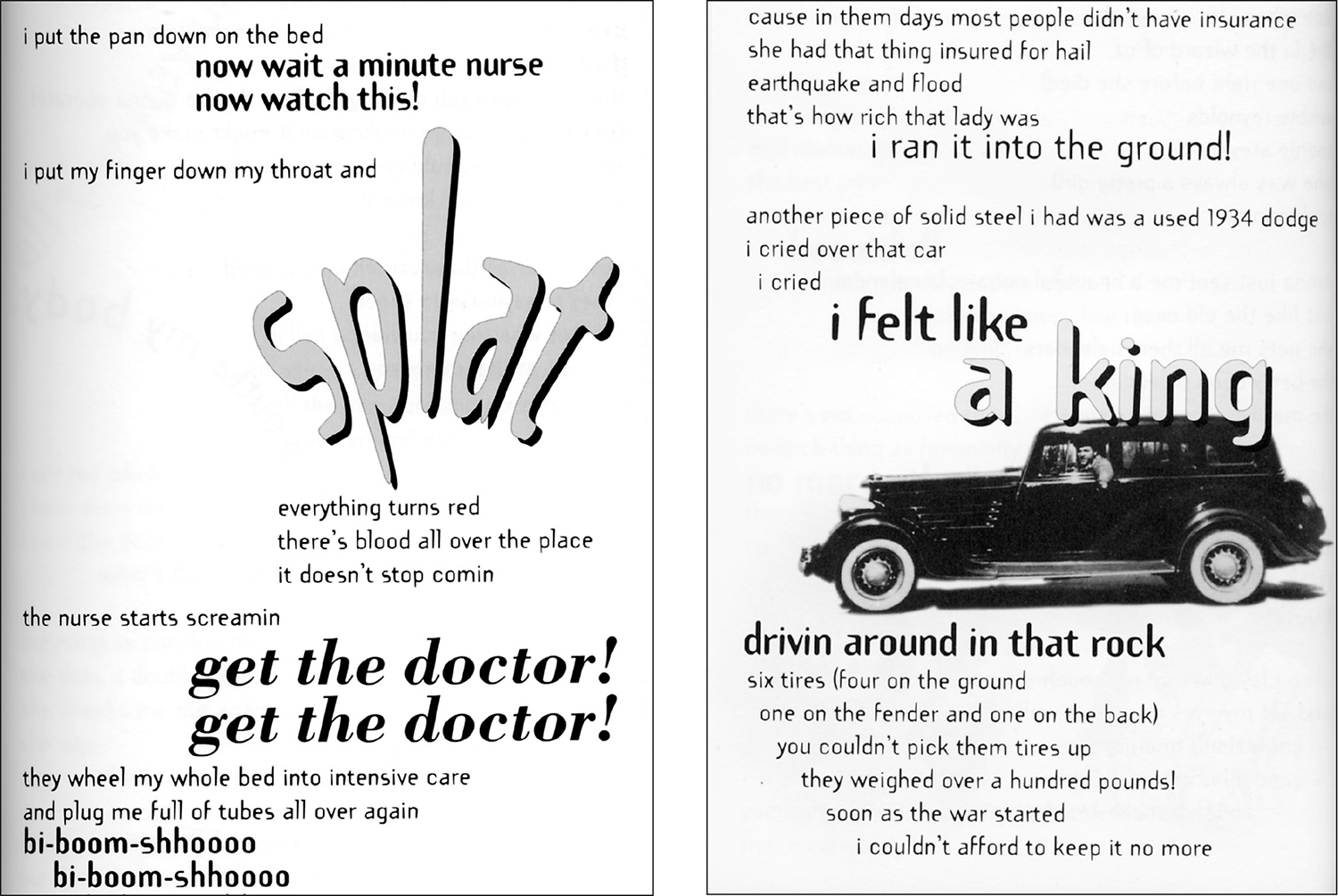

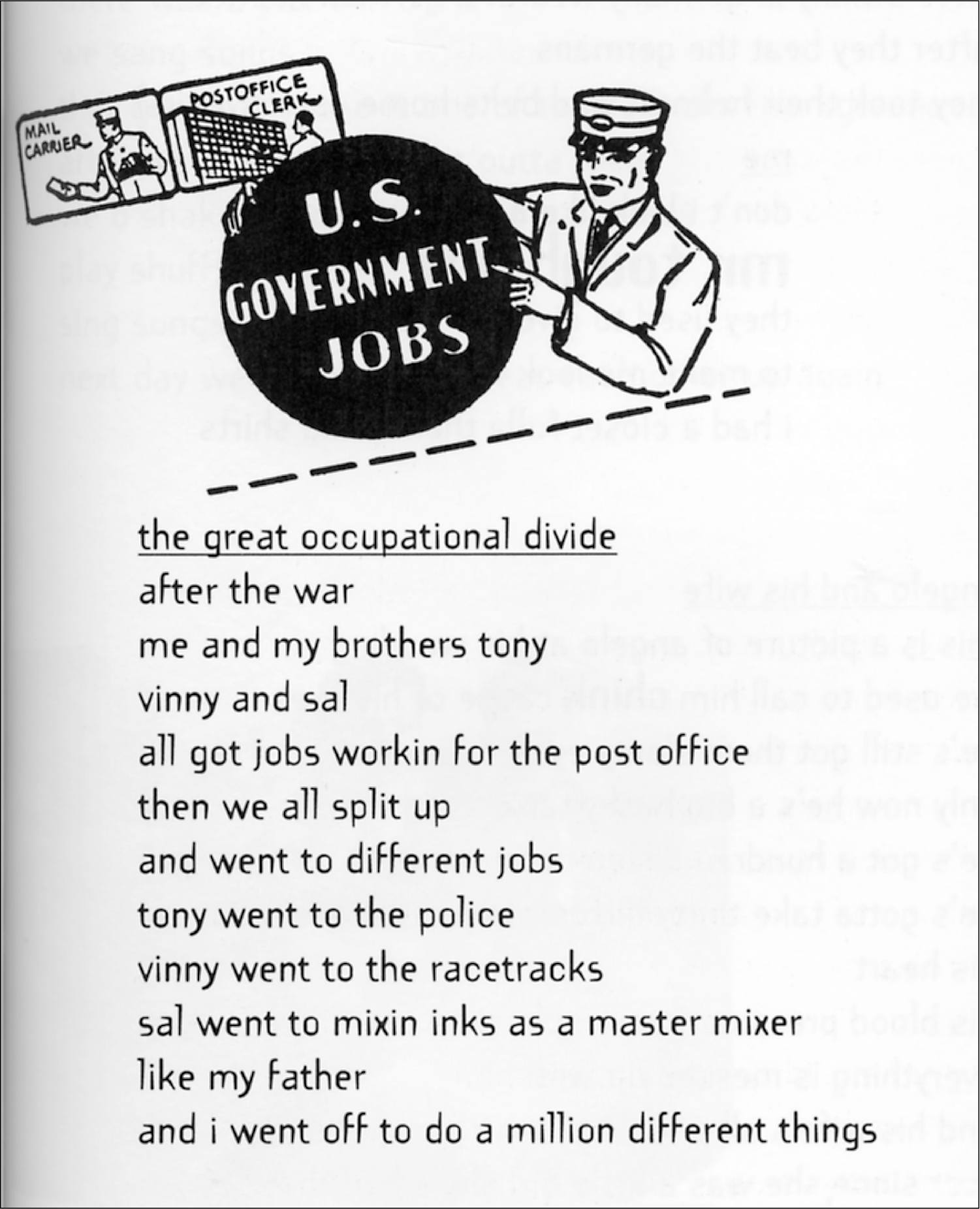

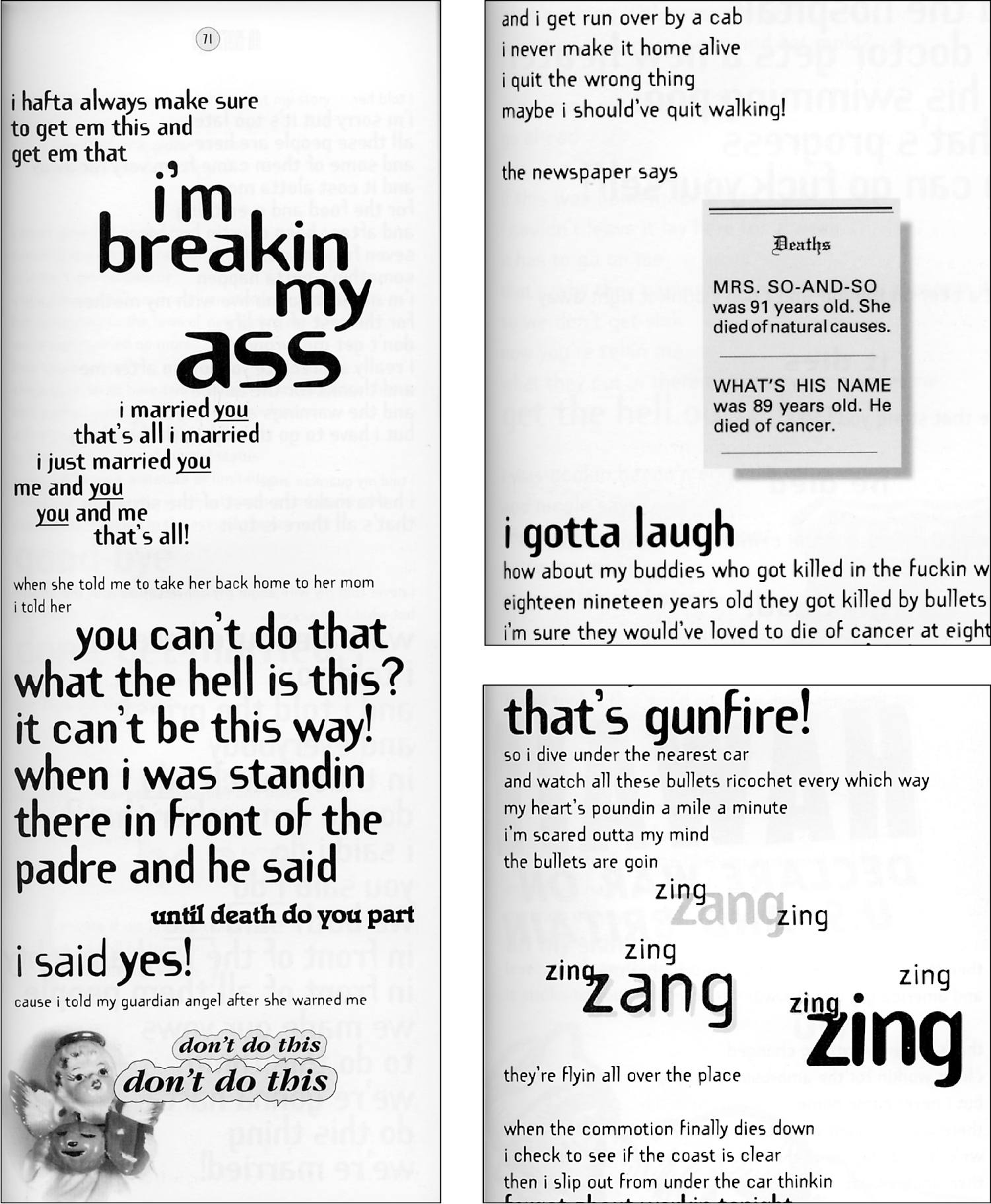

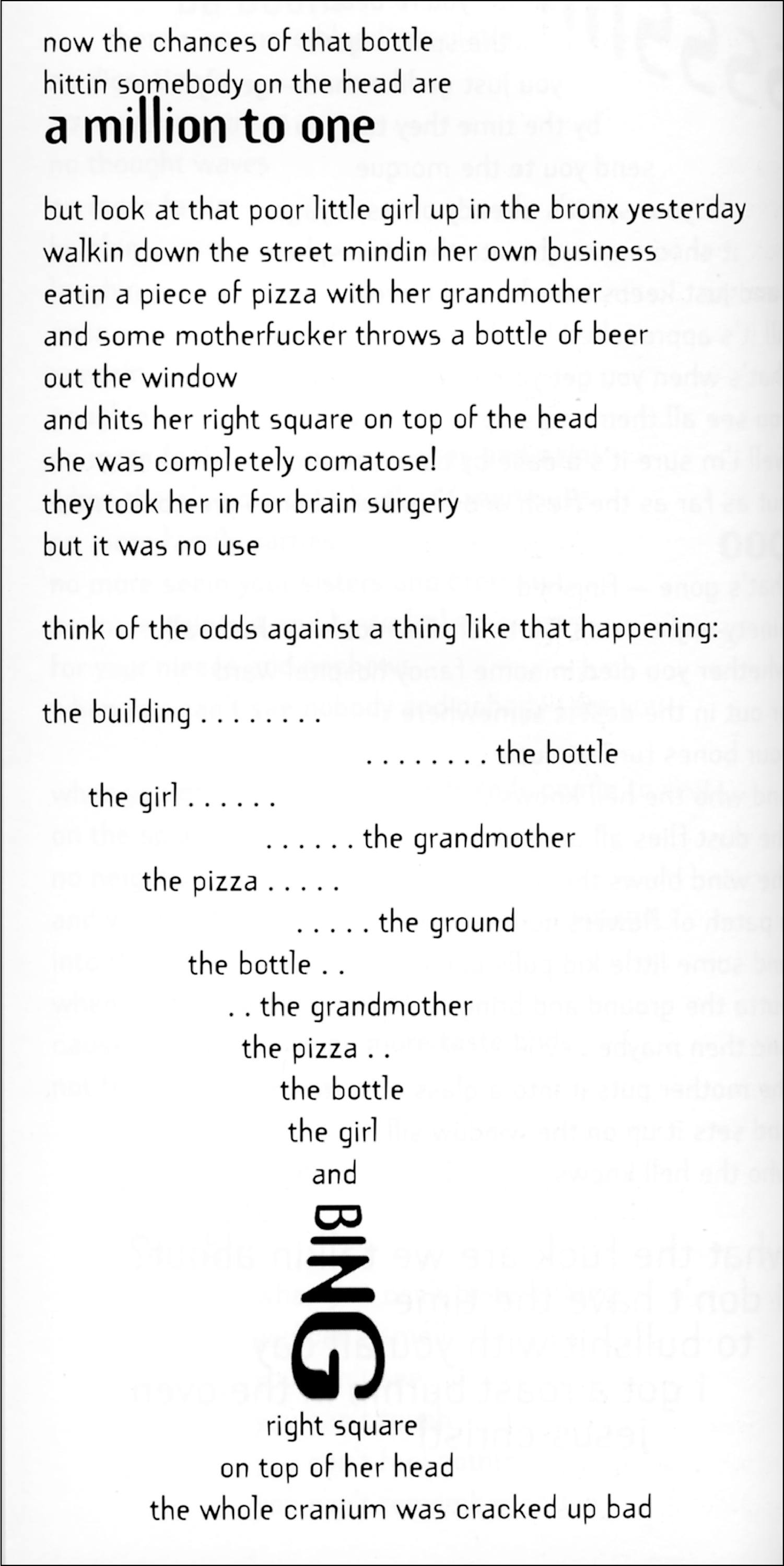

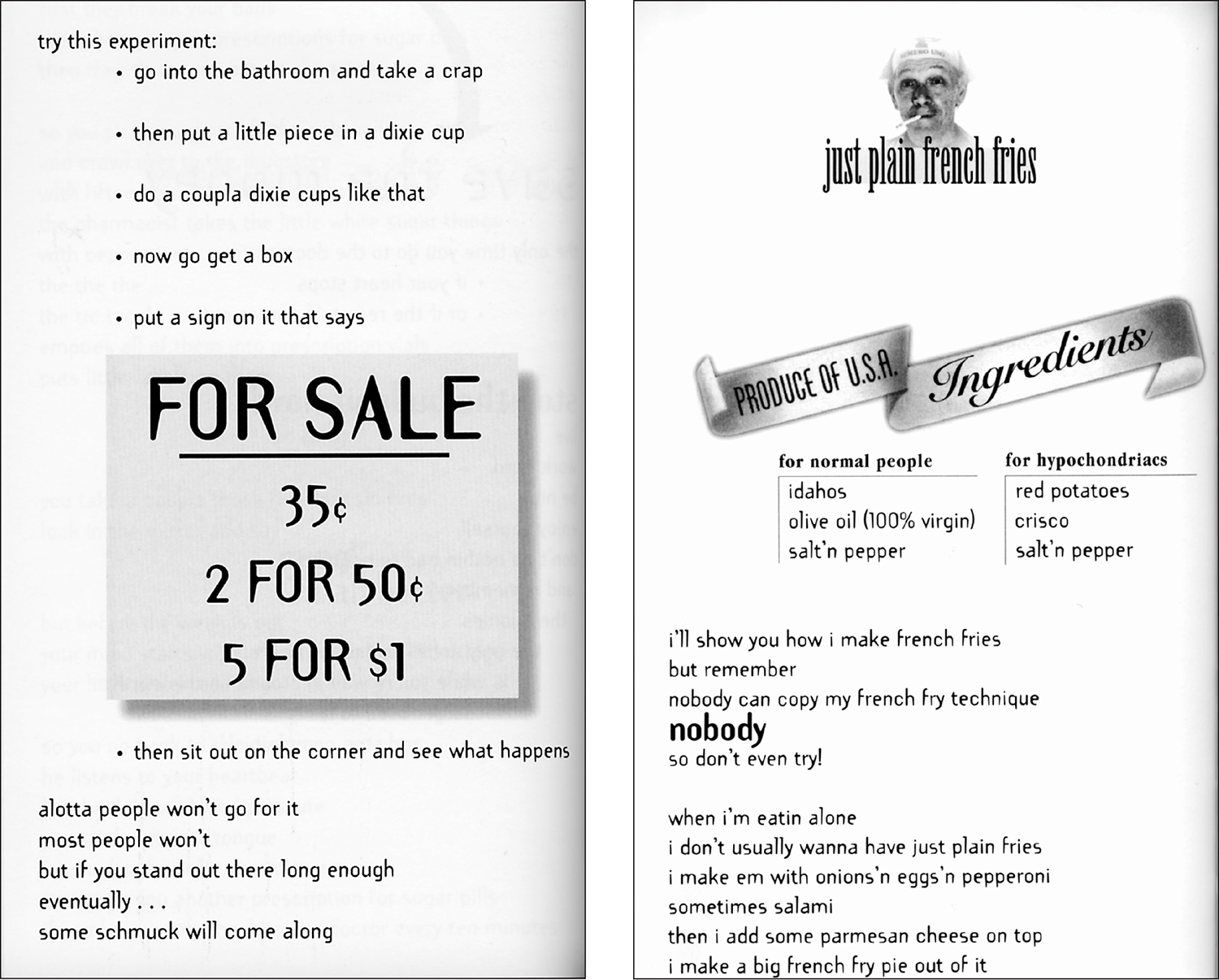

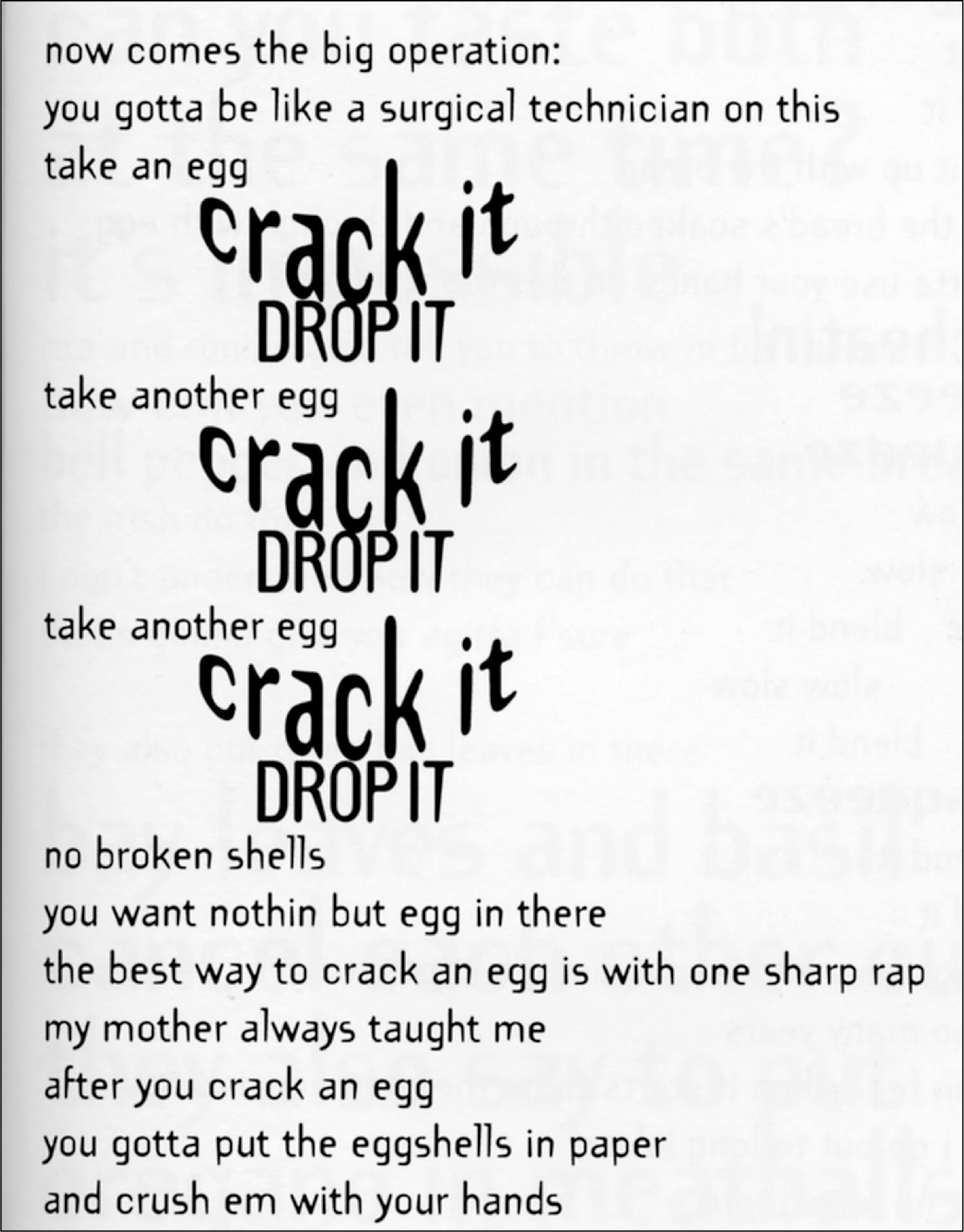

Each book is composed using an idiosyncratic synthesis of storytelling, poetry, typographic design, illustrations, and photographs. Influenced by Dadaism, futurism, and the writing of e.e. cummings, Gertrude Stein, and the American poet and painter Kenneth Patchen, Mr. Lehrer’s books explore the plasticity, the physicality of words and groups of words—words that dart and swoop and blare and recede and curl up and pop out and undulate and zoom across the page.

‘I’m writing in a way that considers the form of thought, the shape of thought, and the shape of speech,’ says Mr. Lehrer. “So, in a way I’m trying to reunite oral tradition with the printed page and, at the same time, discover what does thought look like, what shape does it take?’

Mr. Lehrer makes a distinction between writing book—what he does—and writing texts— what most authors do.

‘When you write a screenplay for film, you’re writing for the medium of film. You’re thinking about scenes as images. You might even be thinking about specific actors and dialogue.

“Or if you’re writing the lyrics to a song, you’re really writing for a song, not writing for a page. But I think people don’t write books, they write texts. They’re not thinking about the structure, the form of a book like you do about a song or film or play. They just think it’s an empty vessel to pour their text into. That’s as far as many people go in terms of considering the form of a book.

‘When I’m composing the book, I think about what it’s like to turn the page. I consider the pacing of a text or of images through time, because books, like film, are a time-space capsule. Things happen through time, and you can use that. You can be aware of that.

‘All writers are aware of that when they are writing a linear story with beginning, middle, and end, but they’re not concerned about it on a visual level and not necessarily on a rhythmic level from page to page and chapter to chapter.’

The visual compositions in The Portrait Series are relatively subdued, compared with what he has done in the past, Mr. Lehrer says, ‘I’ve discovered that most readers are not willing to participate in that kind of interactive read,” he says, “and it was more important to get these stories across than to overwhelm the reader.’

The stories are of men who are neither famous nor, by and large, successful in a conventional sense. ‘I was looking for people who straddled the wobbly line between brilliance and madness–people who have lived through unbelievable circumstances and come out the other end with a fierce passion for life,’ Mr. Lehrer says. His subjects are:

• Brother Blue, an ordained minister who holds degrees from Harvard and Yale and is known as the official storyteller of Boston. “Brother Blue is to storytelling what John Coltrane is to jazz,” Mr. Lehrer wrote.

• Claude Debs, the grandson of Eugene V. Debs, who was orphaned, then adopted by a French diplomat. Sexually abused, Claude ran away at the age of 13. By the time he was 40, he had earned six degrees and “lived the life of a bohemian painter, entrepreneur, film maker, fashion photographer, spy, doctor, philanthropist, homeless person, and a successful businessman,” Mr. Lehrer wrote. “Claude has always been an inventor, a romantic, a schemer, and the hardest worker as well as the most sensuous and oversexed man I’ve ever met.”

• Nicky D., a 72-year-old retired dockworker, whom Mr. Lehrer describes as “hard-boiled and soft-hearted,” full of advice, and offering “an ongoing stream of barbed commentary, argument, reminiscences, and philosophy.”

• Charlie, a gifted musician who has spent over half of his 30 years in and out of mental institutions.

Collectively, they make up a riveting group of eccentrics, people Mr. Lehrer refers to as ‘the stoop philosophers, sit-down comedians, and off-the-cuff bards who puncture the predictability of everyday life.’

Before he revealed to any of the men his interest in telling their stories, he studied them with care. ‘I knew they seemed extremely colorful and unpredictable, which was something that attracted me to them. But sometimes people are broken records.

‘I tape-recorded them at the beginning without their knowing and studied to see if they were not repeating themselves. These people all passed that litmus test.’

Once Mr. Lehrer chose his subjects, he told them what he intended and set up partnerships that include written agreements guaranteeing a percentage of advances and royalties. He began “more consciously collecting their stories through hanging out with them, becoming friends with these people if I hadn’t already been. Eating together, going on long walks, and hanging out.’

He conducted no formal interviews until near the end, when he realized he had to fill holes in their stories. ‘These books are not in any way transcriptions of what they say,’ Mr. Lehrer notes. He says he did use tape recorders to capture some of the talks, but he also could just as easily have a phone conversation during which somebody told him an experience that piqued his interest. ‘And then I would hang up from them and write it into a story using their voice’

He says he has written ‘my view of these people’s view of themselves. So the books read as autobiography in a sense.’ Charlie, ‘remembering’ one of his stays in a children’s psychiatric hospital: ‘Since I’ve been here they’ve tried me out on Thorazine, Haldol, Mellaril, Cogentin, Prolixin, and Trilafon. I feel like there’s a barbed-wire fence inside my body. My mind is dragged across a dirt road by a leash.’

Says Mr. Lehrer, ‘I took the liberties a painter or photographer might take when a subject sits for a portrait. And a turn of phrase, fragmentary memories, years of thought and conversation are crafted, shaped into short stories, diatribes, extended monologues through me.’

He will read it back to them—‘to see if it rings true,’ he says. ‘And they’ll invariably fill in some holes or show me that the logic of what I had thought it was about was even more twisted than I had imagined.’ After that, he continues, it’s like writing a short story or other fiction: ‘There is just a tremendous amount of writing and rewriting until the rhythm of the words, the shape of the trajectory of the story, feels right.’

Brother Blue, remembering the embarrassment he felt as a young boy in church when his father got carried away and began shouting and speaking in tongues: ‘And my father’s goin’ RRRRRHHHHHHHHHH RRRRRRRRRHHHHHHHHHHHHHHH. He’s trying to hold it in but eventually he’s just vibratin’ in his seat. RRRRHHHHHHHHHH RRRRRRRRRHHHHHHHHHHHHHH. Suddenly he just lets go. HALLELUJAH! He starts crying and weepin’ and prayin’ HALLELUJAH HALLELUJAH HALLELUJAH HALLELUJAH. He’s on fire and I’m sinkin’ into my pew getting smaller’n smaller. I barely even exist, I’m so embarrassed’

Brother Blue and the other men who had been so open during the process of writing the books became ‘very nervous’ as press time approached, Mr. Lehrer says. ‘Brother Blue said that when he first went into a bookstore and saw dozens of copies, he felt like disappearing because he was so exposed,’ he says.

But their apprehensions quickly evaporated. ‘Now, after really reading the book several times and getting feedback from people, he says that I’m one of his two angels—his wife, Ruth, and me—who understood him and captured his soul. Brother Blue and Mr. Lehrer have given public readings from the books together.

Nicky D., on his mother: ‘Just before she died, on top of her heart condition and her diabetes, she caught hold of a bad flu. So I called for an ambulance and I’ll never forget as they were takin’ her out of this apartment on a stretcher, the lights swirlin’ all around the block, people gawkin’ at her, she couldn’t even hardly breathe. Was she thinking about herself? No. No. Not at all. Her last words were, ‘Who’s gonna take care of Nicky?’

As Mr. Lehrer writes, he thinks about using line breaks, type size and style, and even empty spaces to heighten, emphasize, or otherwise color the language and the story. ‘I find that people don’t necessarily think or talk in traditional sentence structure, so lineating these texts as poetry, as verse, is more effective at capturing the nature of thought or speech. So I write that way—I will underline or move into an italic or bold as I’m writing, making notes to myself I’ll use later.’

After he has written a piece, he begins composing the visual elements. He has used more than two dozen typefaces in each book. But he uses one typeface for the voice of each character. ‘In a way I audition different typefaces for each book,’ he says. ‘I use one type family per character and so I try different type families for each of the characters until one gets the part, gets typecast.’ He’s looking, he says, ‘for a typeface that’s versatile enough to give me a sense of the character, the age of the person, the personality, the texture of the voice.’

Charlie’s personality was so ‘mercurial,’ he says, that he ended up changing the typeface for his portrait only two months before the book was published. ‘His typeface just kept changing. I ended up using Gill Sans, but at one time I had Futura,’ he says. Futura didn’t work because ‘the face was a little too severe,’ he explains. ‘I wanted something a little softer.’

Only a few pages into any of Mr. Lehrer’s four portraits, you begin to experience a strange sensation: You hear the characters in your mind. You’re drawn in. You’re in the conversation with them. You hear them talking to you. their stories echo in your mind long after the sound of them has ceased: the teenaged Charlie, alone and ignored in an isolation chamber, having an allergic reaction to Thorazine: Brother Blue escorting his father to the hospital to have a bullet removed from his head—the result of a botched suicide attempt; 12-year-old Claude’s story of befriending a baby monkey in a sheik’s desert compound and then watching helplessly as it is killed and served for dinner: ‘a volcano was erupting inside my body and yet / I just sat there / I sat there and watched as everybody took their little hammers one at a time and crashed them down into zuzu’s howling / screeching / screaming / bloody head . . . I made believe that night / I learned how to really make believe / that was the night I learned how to really fake it / how to bite the tongue that needs to scream. . . .’”

The Chronicle of Higher Education Zoe Ingalls

Update:

Sadly, Nicky D. died in 2009.

He leaves a lasting presence.

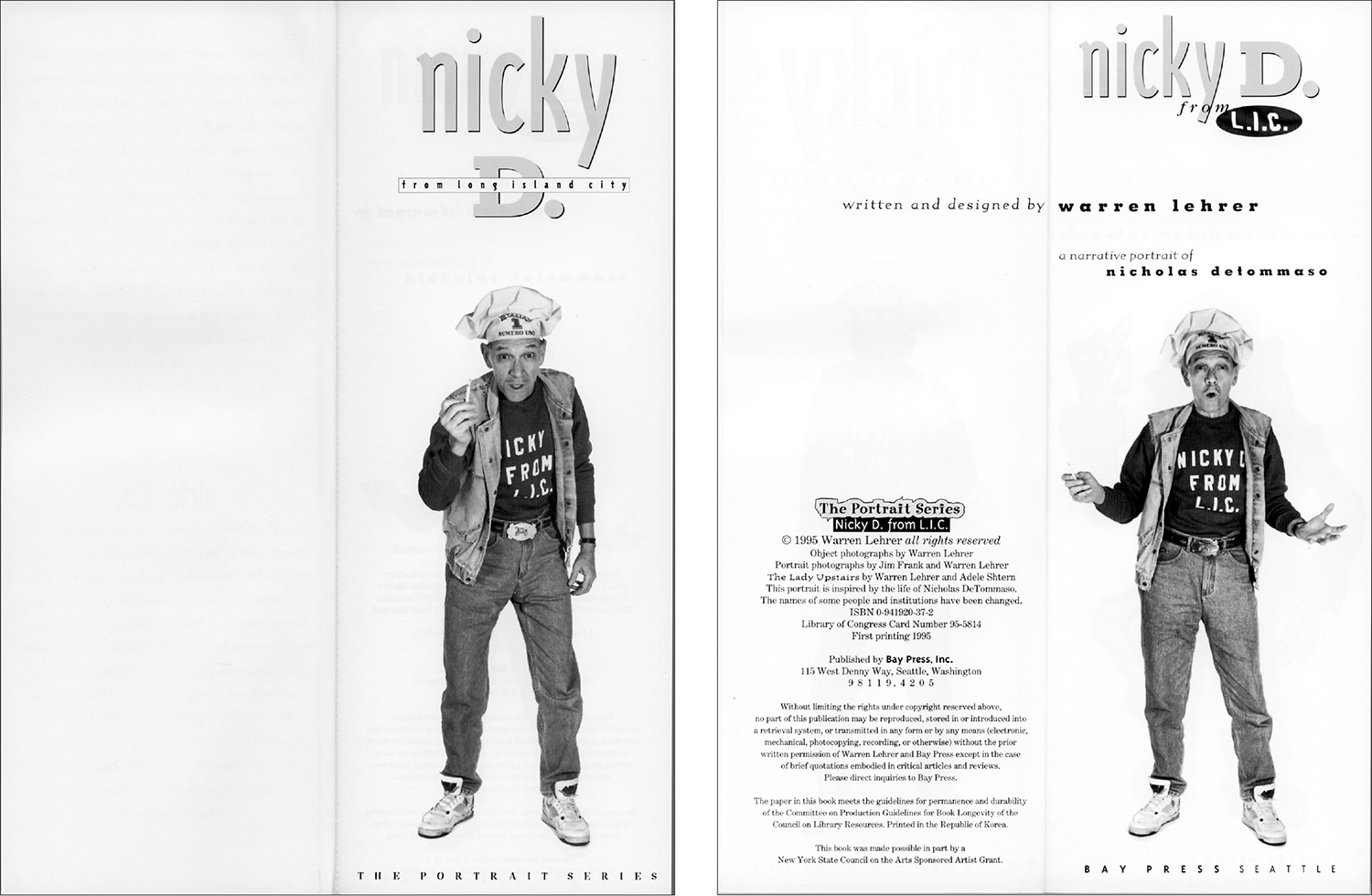

Nicky D from L.I.C.: A Narrative Portrait of Nicholas Detommaso

Written and designed by Warren Lehrer.

Published 1995 by Bay Press

6.5” x 9.75” x 261 pages. Paperback. Four color cover. One interior (black).

Part of the Portrait Series.

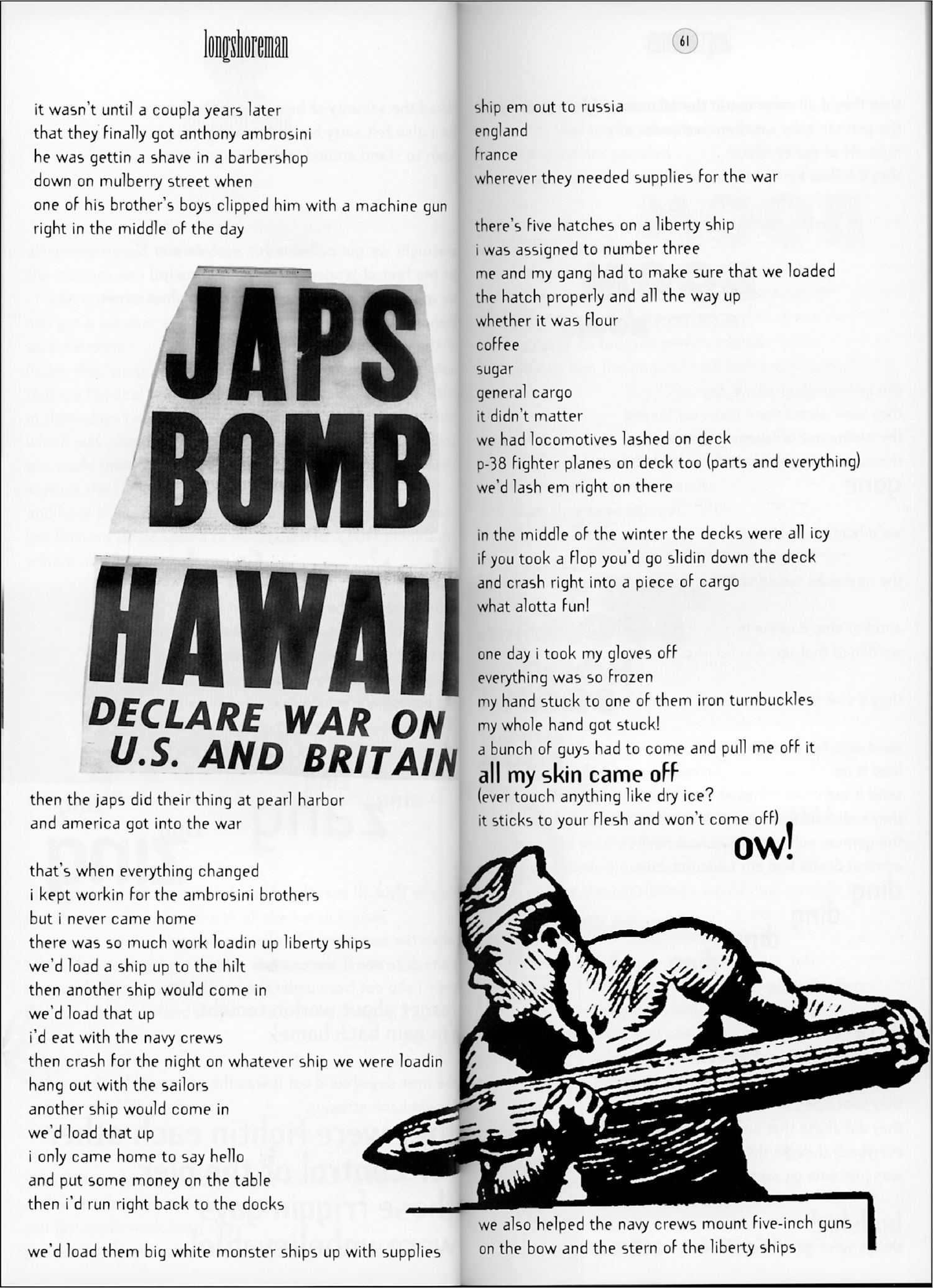

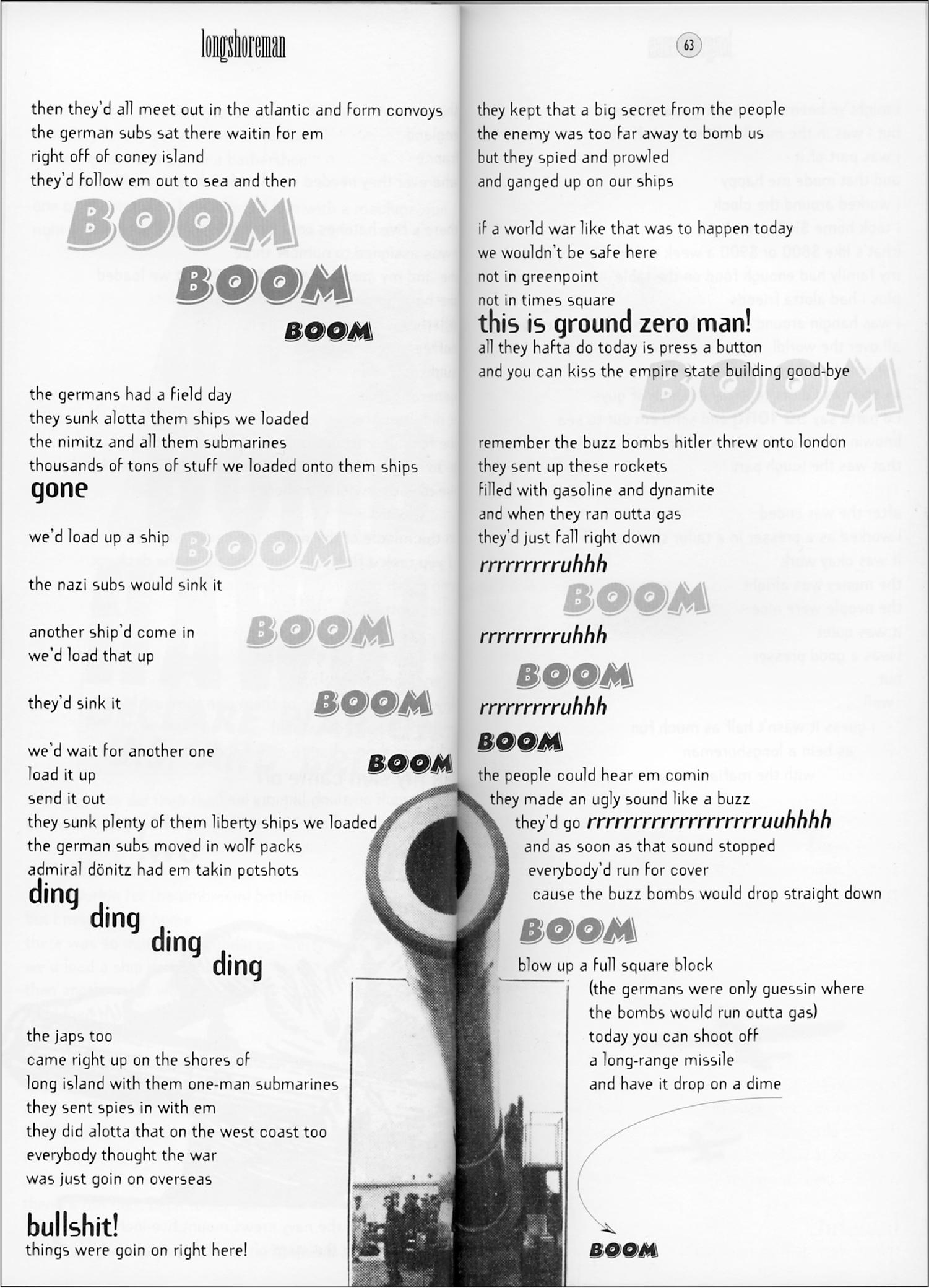

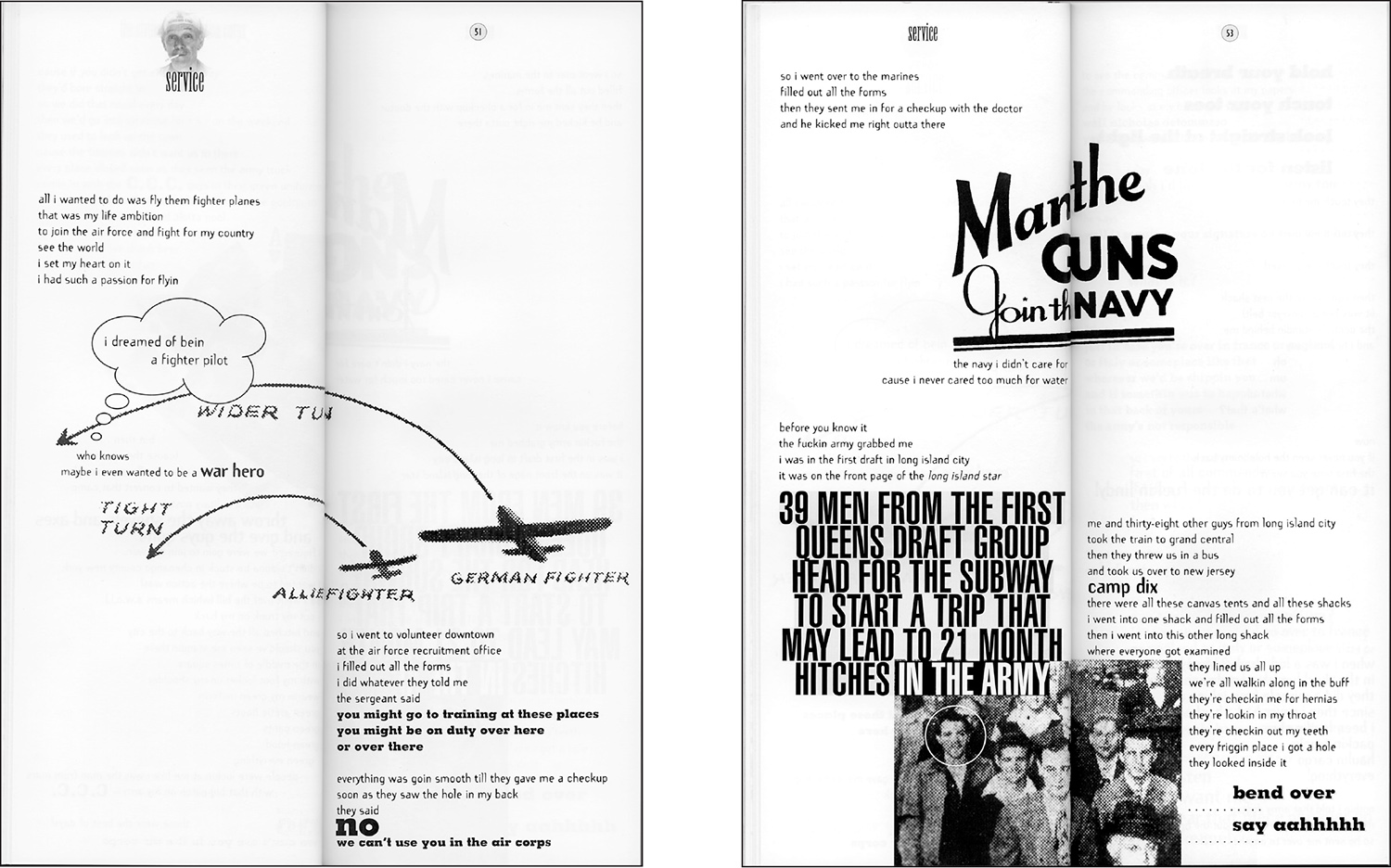

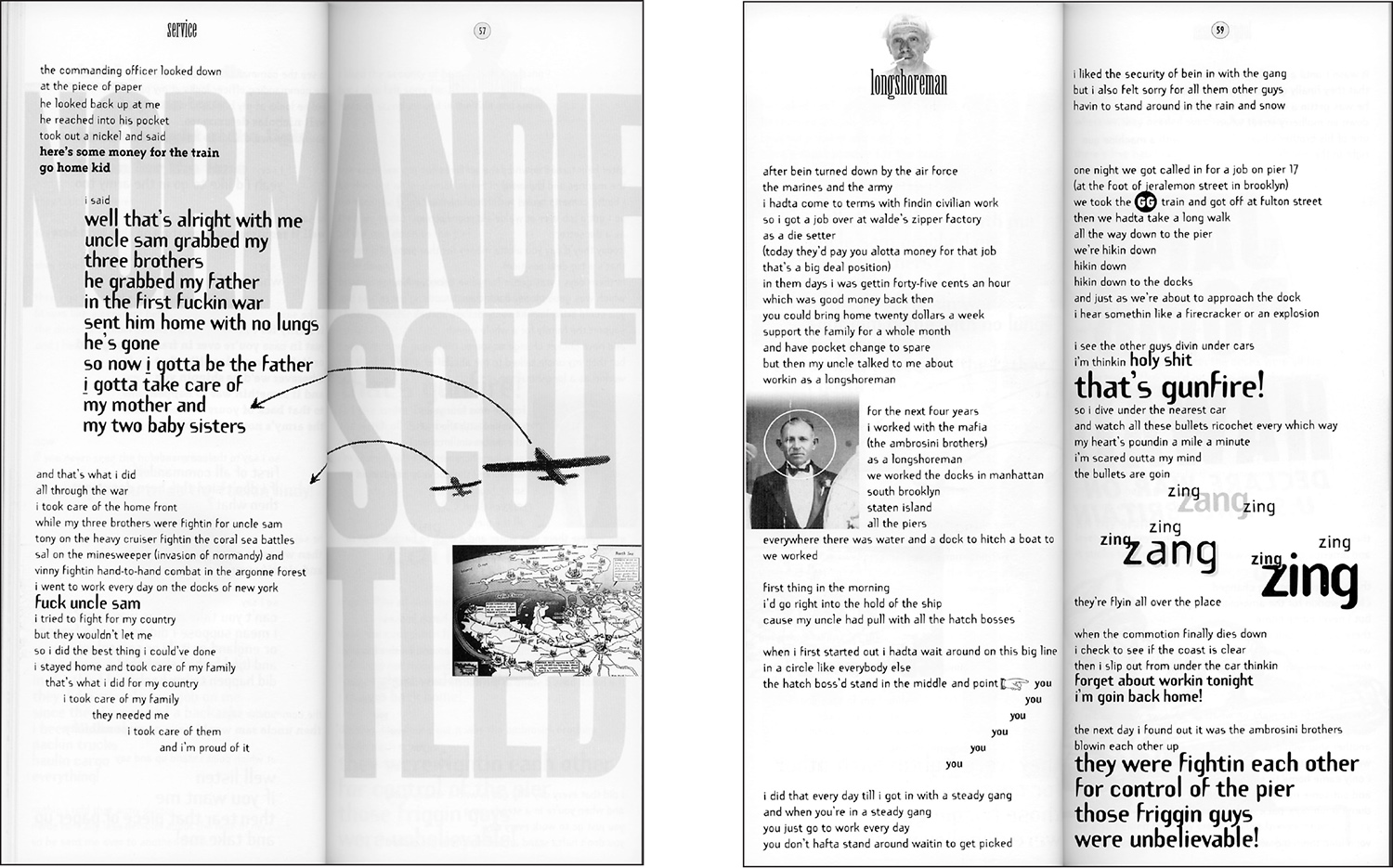

Based on a hard-boiled, soft-hearted, retired dock worker who expounds on his life story and meaning of life from his four room railroad flat in Long Island City, New York, where’s he’s lived for over seventy years. Surrounded by memorabilia and seasonal icons of good cheer, Nicholas Detommaso delivers a continuous stream of barbed commentary on familial duty, work, war, money, religion—and the best way to chop garlic. Undiminished by a childhood spent in and out of hospitals, a lifetime of backbreaking work, and his share of disappointments, this irascible stoop philosopher and sit-down comedian reveals a tender regard for friends and family, and a stubborn inclination for life. Replete a few of his ‘famous recipes.’

ISBN 0-941920-37-2

BUY NOW Suggested Retail Price: $12.99 + $3 shipping and handling

BUY NOW Portrait Series: 4 book set, Special Sale: $25 + shipping and handling

[includes: Brother Blue: A Narrative Portrait of Brother Blue; Nicky D. from L.I.C.: A Narrative Portrait of Nicholas Detommaso; Claude: A Narrative Portrait of Claude Debs; Charlie: A Narrative Portrait of Charles Lang]

sample page spreads and details

“…Lehrer’s most recent project is a quartet of books called The Portrait Series, published by Bay Press in Seattle. In each volume, a man on the “wobbly line between brilliance and madness” narrates his biography. Brother Blue is an ordained minister and professional raconteur who dresses in clothes trimmed with butterflies. Charlie, a musician, has been in and out of mental institutions for 17 years. Nicky D. is a retired dockworker in Long Island City, Queens, who delivers ‘barbed commentary on familial duty, work, war, money, religion—and the best way to chop garlic.’ Claude, the adopted son of a French ambassador, earned degrees in art and medicine and endured a spate of homelessness.

The Portrait Series represents Mr. Lehrer’s first attempt to reach a mainstream audience. His early work was published in editions of under a thousand and sold to collectors who recognized the author’s place in a long tradition of typographic outlaws. Others considered him too far ahead of his time. When he showed his first book Versations to a dealer more than a decade ago, the man admired its artful density, then advised Mr. Lehrer, “Come back when you’re dead.”

Now the times are beginning to catch up to him… While Mr. Lehrer’s early books can seem as boisterous as a video arcade—one does not read them so much as attend their performance—The Portrait Series shows more typographic restraint. It also shamelessly offers the pleasures of voyeurism all good books afford. Who knows? Mr. Lehrer may finally have met the times halfway.”

The New York Times Book Review Julie Lasky

“In the four new publications by Lehrer… the implications of a new kind of literature are at last being pursued… The Portrait Series is articulated with enormous feeling and care by an author with an ear superbly attuned to the cadences of spoken language. Lehrer, unlike so many contemporary graphic stylists, begins from a deep engagement with content he has created himself…”

Frieze Magazine Rick Poynor

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

From the introduction to Nicky D. from L.I.C.: a narrative portrait of Nicholas DeTommaso

You don’t knock. That’s an insult. If it’s any time between six a.m. and eleven p.m. the policy is open door. Just push. Once inside Nicky D.’s four-room railroad flat, you’ve entered a never-never land of cartoon characters, nursery rhymes, angels, saints, monsters, Hollywood divas, and Coca-Cola girls. Depending on the time of year, every wall and ceiling is profusely adorned with the appropriate icons of good cheer (be they goblins and skeletons, Santa Clauses and Christmas lights, turkeys and pilgrims, Easter eggs and bunnies, or birthday mementos for all the Libras in the family).

Nicky D. is either in the kitchen with his sleeves rolled up, preparing the next meal to the cackle of talk radio, or he’s all the way down the other end of the apartment, feet up on the coffee table, a Marlboro hanging from his lips, going through yesterday’s race results in The Daily News with the TV tuned to a colorized movie from the forties. The aroma of Nicky D’s famous Italian home cooking fills the dimly lit, venetian-blinded air. Stuffed chocolate samplers, candies of all stripes, and bubblegum offer themselves up to you from covered glass jars at every turn. Retirement is saying yes to all those things he couldn’t do during a lifetime of hard work loading and unloading stuff from here to there.

At seventy-two, with the help of daily iron pills and an inside deal with God, Nicky D. has more energy than most people I know half his age. Still, he prefers to bask (and stew) in the comfort of his own home. Before it became his own private “Shangri-la,” Nicky shared this apartment in Long Island City, Queens, with his mother, three brothers, and two sisters. Before that, he lived for eight years within the mural-filled walls of the pediatric ward of an orthopedic hospital. Memories of all those years flash before him more frequently these days. Even with growing up sick, the wars, no father, very little money, and no privacy, those were good years.

Today, all that really matters are his thirty-five nieces and nephews and a handful of neighbors and friends. We are the recipients of his food, his Mr. Fixit service (free of charge), and an ongoing stream of barbed commentary, argument, reminiscences, and philosophy. No need to knock. Just turn the page.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

“The arrival of the first set of Warren Lehrer’s Portrait Series is something of an event… echoes of Henry Miller… vivid evocations of family life and history. Absolutely defining and unmistakable.”

JAB (Journal of Artists’ Books) Paul Zelevansky

“Each book in The Portrait Series is a vibrant visual and narrative biography of an eccentric, prismatic and resilient personality… Riveting! Lehrer defies categorization.”

Gannet Newspapers Linda Kaplan Wagner

“With The Portrait Series Lehrer continues his pioneering work in ‘visual literature’ in which the look of the words on the page is as important as the words themselves.”

Philadelphia City Paper David Warner

“As an undergraduate art major at Queens College of the City University of New York in the 1970s, Warren Lehrer experimented with drawings that combined words and images. He amassed, he says, ‘a whole stack of secret drawings I never showed anybody.’

Then one day he showed them to his painting teacher. ‘The teacher wagged his finger in my face and said, ‘You’re a really good student, but you’re barking up the wrong tree. Don’t ever combine words and images. They’re two different languages, and they should stay separate.’”

Mr. Lehrer recalls. ‘I left his office feeling like I’d been given a mission in life. And I’ve been combining words and images every since.’

Mr. Lehrer, now 40, is an associate professor of art at the State University of New York at Purchase. He teaches design, typography, book arts, performance art, and public art, as well as an interdisciplinary workshop for artists and writers.

Disregarding his professor’s admonition, Mr. Lehrer has combined words and images in a total of 10 books that defy conventional notions of writing and book making. His most recent effort is The Portrait Series, published by Bay Press, Inc. The series consists of four books, each a profile of a man, written by Mr. Lehrer, but presented as an autobiographical, first-person monologue. (Mr. Lehrer is at work on a series of portraits of women.)

Each book is composed using an idiosyncratic synthesis of storytelling, poetry, typographic design, illustrations, and photographs. Influenced by Dadaism, futurism, and the writing of e.e. cummings, Gertrude Stein, and the American poet and painter Kenneth Patchen, Mr. Lehrer’s books explore the plasticity, the physicality of words and groups of words—words that dart and swoop and blare and recede and curl up and pop out and undulate and zoom across the page.

‘I’m writing in a way that considers the form of thought, the shape of thought, and the shape of speech,’ says Mr. Lehrer. “So, in a way I’m trying to reunite oral tradition with the printed page and, at the same time, discover what does thought look like, what shape does it take?’

Mr. Lehrer makes a distinction between writing book—what he does—and writing texts— what most authors do.

‘When you write a screenplay for film, you’re writing for the medium of film. You’re thinking about scenes as images. You might even be thinking about specific actors and dialogue.

“Or if you’re writing the lyrics to a song, you’re really writing for a song, not writing for a page. But I think people don’t write books, they write texts. They’re not thinking about the structure, the form of a book like you do about a song or film or play. They just think it’s an empty vessel to pour their text into. That’s as far as many people go in terms of considering the form of a book.

‘When I’m composing the book, I think about what it’s like to turn the page. I consider the pacing of a text or of images through time, because books, like film, are a time-space capsule. Things happen through time, and you can use that. You can be aware of that.

‘All writers are aware of that when they are writing a linear story with beginning, middle, and end, but they’re not concerned about it on a visual level and not necessarily on a rhythmic level from page to page and chapter to chapter.’

The visual compositions in The Portrait Series are relatively subdued, compared with what he has done in the past, Mr. Lehrer says, ‘I’ve discovered that most readers are not willing to participate in that kind of interactive read,” he says, “and it was more important to get these stories across than to overwhelm the reader.’

The stories are of men who are neither famous nor, by and large, successful in a conventional sense. ‘I was looking for people who straddled the wobbly line between brilliance and madness–people who have lived through unbelievable circumstances and come out the other end with a fierce passion for life,’ Mr. Lehrer says. His subjects are:

• Brother Blue, an ordained minister who holds degrees from Harvard and Yale and is known as the official storyteller of Boston. “Brother Blue is to storytelling what John Coltrane is to jazz,” Mr. Lehrer wrote.

• Claude Debs, the grandson of Eugene V. Debs, who was orphaned, then adopted by a French diplomat. Sexually abused, Claude ran away at the age of 13. By the time he was 40, he had earned six degrees and “lived the life of a bohemian painter, entrepreneur, film maker, fashion photographer, spy, doctor, philanthropist, homeless person, and a successful businessman,” Mr. Lehrer wrote. “Claude has always been an inventor, a romantic, a schemer, and the hardest worker as well as the most sensuous and oversexed man I’ve ever met.”

• Nicky D., a 72-year-old retired dockworker, whom Mr. Lehrer describes as “hard-boiled and soft-hearted,” full of advice, and offering “an ongoing stream of barbed commentary, argument, reminiscences, and philosophy.”

• Charlie, a gifted musician who has spent over half of his 30 years in and out of mental institutions.

Collectively, they make up a riveting group of eccentrics, people Mr. Lehrer refers to as ‘the stoop philosophers, sit-down comedians, and off-the-cuff bards who puncture the predictability of everyday life.’

Before he revealed to any of the men his interest in telling their stories, he studied them with care. ‘I knew they seemed extremely colorful and unpredictable, which was something that attracted me to them. But sometimes people are broken records.

‘I tape-recorded them at the beginning without their knowing and studied to see if they were not repeating themselves. These people all passed that litmus test.’

Once Mr. Lehrer chose his subjects, he told them what he intended and set up partnerships that include written agreements guaranteeing a percentage of advances and royalties. He began “more consciously collecting their stories through hanging out with them, becoming friends with these people if I hadn’t already been. Eating together, going on long walks, and hanging out.’

He conducted no formal interviews until near the end, when he realized he had to fill holes in their stories. ‘These books are not in any way transcriptions of what they say,’ Mr. Lehrer notes. He says he did use tape recorders to capture some of the talks, but he also could just as easily have a phone conversation during which somebody told him an experience that piqued his interest. ‘And then I would hang up from them and write it into a story using their voice’

He says he has written ‘my view of these people’s view of themselves. So the books read as autobiography in a sense.’ Charlie, ‘remembering’ one of his stays in a children’s psychiatric hospital: ‘Since I’ve been here they’ve tried me out on Thorazine, Haldol, Mellaril, Cogentin, Prolixin, and Trilafon. I feel like there’s a barbed-wire fence inside my body. My mind is dragged across a dirt road by a leash.’

Says Mr. Lehrer, ‘I took the liberties a painter or photographer might take when a subject sits for a portrait. And a turn of phrase, fragmentary memories, years of thought and conversation are crafted, shaped into short stories, diatribes, extended monologues through me.’

He will read it back to them—‘to see if it rings true,’ he says. ‘And they’ll invariably fill in some holes or show me that the logic of what I had thought it was about was even more twisted than I had imagined.’ After that, he continues, it’s like writing a short story or other fiction: ‘There is just a tremendous amount of writing and rewriting until the rhythm of the words, the shape of the trajectory of the story, feels right.’

Brother Blue, remembering the embarrassment he felt as a young boy in church when his father got carried away and began shouting and speaking in tongues: ‘And my father’s goin’ RRRRRHHHHHHHHHH RRRRRRRRRHHHHHHHHHHHHHHH. He’s trying to hold it in but eventually he’s just vibratin’ in his seat. RRRRHHHHHHHHHH RRRRRRRRRHHHHHHHHHHHHHH. Suddenly he just lets go. HALLELUJAH! He starts crying and weepin’ and prayin’ HALLELUJAH HALLELUJAH HALLELUJAH HALLELUJAH. He’s on fire and I’m sinkin’ into my pew getting smaller’n smaller. I barely even exist, I’m so embarrassed’

Brother Blue and the other men who had been so open during the process of writing the books became ‘very nervous’ as press time approached, Mr. Lehrer says. ‘Brother Blue said that when he first went into a bookstore and saw dozens of copies, he felt like disappearing because he was so exposed,’ he says.

But their apprehensions quickly evaporated. ‘Now, after really reading the book several times and getting feedback from people, he says that I’m one of his two angels—his wife, Ruth, and me—who understood him and captured his soul. Brother Blue and Mr. Lehrer have given public readings from the books together.

Nicky D., on his mother: ‘Just before she died, on top of her heart condition and her diabetes, she caught hold of a bad flu. So I called for an ambulance and I’ll never forget as they were takin’ her out of this apartment on a stretcher, the lights swirlin’ all around the block, people gawkin’ at her, she couldn’t even hardly breathe. Was she thinking about herself? No. No. Not at all. Her last words were, ‘Who’s gonna take care of Nicky?’

As Mr. Lehrer writes, he thinks about using line breaks, type size and style, and even empty spaces to heighten, emphasize, or otherwise color the language and the story. ‘I find that people don’t necessarily think or talk in traditional sentence structure, so lineating these texts as poetry, as verse, is more effective at capturing the nature of thought or speech. So I write that way—I will underline or move into an italic or bold as I’m writing, making notes to myself I’ll use later.’

After he has written a piece, he begins composing the visual elements. He has used more than two dozen typefaces in each book. But he uses one typeface for the voice of each character. ‘In a way I audition different typefaces for each book,’ he says. ‘I use one type family per character and so I try different type families for each of the characters until one gets the part, gets typecast.’ He’s looking, he says, ‘for a typeface that’s versatile enough to give me a sense of the character, the age of the person, the personality, the texture of the voice.’

Charlie’s personality was so ‘mercurial,’ he says, that he ended up changing the typeface for his portrait only two months before the book was published. ‘His typeface just kept changing. I ended up using Gill Sans, but at one time I had Futura,’ he says. Futura didn’t work because ‘the face was a little too severe,’ he explains. ‘I wanted something a little softer.’

Only a few pages into any of Mr. Lehrer’s four portraits, you begin to experience a strange sensation: You hear the characters in your mind. You’re drawn in. You’re in the conversation with them. You hear them talking to you. their stories echo in your mind long after the sound of them has ceased: the teenaged Charlie, alone and ignored in an isolation chamber, having an allergic reaction to Thorazine: Brother Blue escorting his father to the hospital to have a bullet removed from his head—the result of a botched suicide attempt; 12-year-old Claude’s story of befriending a baby monkey in a sheik’s desert compound and then watching helplessly as it is killed and served for dinner: ‘a volcano was erupting inside my body and yet / I just sat there / I sat there and watched as everybody took their little hammers one at a time and crashed them down into zuzu’s howling / screeching / screaming / bloody head . . . I made believe that night / I learned how to really make believe / that was the night I learned how to really fake it / how to bite the tongue that needs to scream. . . .’”

The Chronicle of Higher Education Zoe Ingalls

Update:

Sadly, Nicky D. died in 2009.

He leaves a lasting presence.